Witnesses to LA History (1996)

A student-produced public art project by the UCLA/ César Chávez Center Digital/ Mural Lab @ the Social and Public Art Resource Center

Conducted by Professor Judith F. Baca

The Collaboration of Souls

My individual desolate-melancholical body cannot contain us…

Life takes over and my body dies.

Exciting death: the dark womb.

Birth appears into our hands;

An implement for our creation.

Look at what we have created!

Beauty,

Magic,

Life and death,

Souls,

Witnesses,

Art and Words

I am the new life . . . My somber body is dead

And my souls take their first breath . . .

My hands, minds and mouths labor in motion

As we gesture a single image, thought, concept.

We are an incarnation of cells in this presence;

At this moment.

-Laura M. Dueñas

The following is written by

Laura M. Dueñas class participant, poet & artist

Jeanette Conchas class participant, poet & artist

It is through the hands of writers and artists that inspiration brings forth words and images. But inspiration does not come from a single mind or element. Inspiration comes best from an exchange of ideas and thoughts; a meeting of hearts. This process of collaboration is one that empowers the mind; feeding it with the different sorts of knowledge that we each possess. Furthermore, through collaboration that allows for the expression of each of our individual notions and concepts emerges a victorious union of creation.

Throughout history, struggles for empowerment have taken place through the process of working collectively. César Chávez set a great example of this. After founding the National Farm Workers Association (NFW), he teamed up with Larry Itliong, head of the Pilipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), merging the organizations to form the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee. The UFW still lives on today, working for and with the people who plant and harvest the food that feeds our nation. Such grass roots organizations are the epitome of triumphant communal collaborations. The collaborative process is a powerful one because it unifies participants who then learn from one another. Working together in such a setting enabled us as a group to create a diverse product that has meaning, history and voice.

We, the students of the UCLA César Chávez Center’s first Mural Digital Imaging class present this record of our efforts . . .

The collaboration of the UCLA’s César Chávez Center, an interdisciplinary department for Chicana/o Studies majors; The Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), which offers students and opportunity to create murals by a collective process; and Cornerstone Theater Company (CTC), a community-based theater; exemplifies how different organizations can work collectively to produce a creative work. The diversity of the students, as portrayed in our images, sketches, thoughts, beliefs and ideas, and the collaborations with each other, brought forth distinct concepts for the final layout of our pieces.

[accordiongroup][accordion title =”Process”]PROCESS

Making the eight murals was not easy. The production of these works took a great deal of time, hard work, and collective decision. There was much brainstorming, planning, research, and designing to be done. When we first met as a class, we didn’t know anything about each other nor how to go about studying and working within a community setting to produce public artworks. Our first step was to acquaint ourselves with each other and develop a feel for how we might work together. Our professor, Judith F. Baca, conceived an activity which helped to synchronize our collaborative endeavor. We responded passionately to this activity expressing ourselves with every possible emotion that was within us. We began to feel comfortable with each other and with ourselves.

Students were asked to write on index cards the ten most significant events that occurred in our lives that made us who we are today. These cars were placed randomly on the wall. It was amazing to see our collective experiences. Then students organized the cards into categories – loss of love, experiences of discrimination, reclaiming our culture, etc., which then became shared experiences. Students then chose a category and discussion groups were formed. Each of these “shared experience” groups then presented their new perspective with the rest of the class. Passionate dialogue ensued.

We then met with a Cornerstone Theater Company representative. CTC works in collaboration with members of divers communities across the country. Their creative process involves establishing direct connections to audiences, engaging them in the challenging and community-building process of crafting great art which reflects the culture and concerns of shared communities. CTC created a production entitled the birthday of the Century, a play that was performed at the California Plaza in downtown Los Angeles, and our task was to create backdrop pieces for the set.

As a class, we visited the site of the play to meet with the California Plaza representatives and with the set designer for the cornerstone Theater Company. Although Cornerstone have us a general idea of the shades of color and images they wanted, we wanted to exercise control over our artistic product, and therefore took the initiative to incorporate our ideas into the design. We were given blueprints of California Plaza, which our technical group used to determine the best size and placement for integration into the architecture. Our next step was to launch into our research phase as a prelude to the actual mural production.

Our research was conducted with reference to the Birthday of the Century script. From there, we brainstormed and outlined our ideas and some facts of Los Angeles history. We also discussed issues on the actual size of the panels, how many panels we would create, where we would place them, and the theme of the painted and digital panels. We gathered our research and facts; student commentaries were taken note of, which helped generate ideas for each of the pieces. Decisions had to be made by all of us in the class: It wasn’t just one individual deciding. Although concepts were similar, we had many different ideas for each of the images.

We concluded that we would create two painted panels to represent birth and death and six digital murals depicting the witnesses to Los Angeles history.

We first worked on the death and birth pieces: these concepts were derived from the theme of the Birthday of the Century play and the theater company’s need to have entrance and exit portals onstage. We researched the various myths, symbols, ideas and theories on death and birth from diverse cultures. Our research was conducted and gathered by pouring through books and magazines and drawing upon our own knowledge. Individuals from each research group shared their ideas with the class. We then had a framework to build upon. We took our themes to the “drawing board” and we sketched and noted them on paper.

We then came to a decision on the images themselves: the Birth Portal and the Death Portal. We took the final chosen images and used the blue-tracing grid technique. We then had to decide on the color treatments for these two prospective acrylic murals. Everyone took a blueprint of the design and did a color treatment. The most successful elements of many different colorations made up the final. Afterwards, we transferred the blueline to the actual surface using charcoal. The entire class helped with the painting and the completion of the death and birth acrylic panels. These two images acted as part of the set for the Cornerstone play.

The remaining six panels were produced digitally and served as witnesses to Death and Birth panels and to the history of Los Angeles. These panels, like the painted ones, took an extensive amount of research and dedication.

We first had to decide which witnesses we were going to use. Exploring the diverse cultures we might portray, we broke up into groups to work on specific areas of research. Each group then presented to the entire class their ideas, pictures, shared experiences, words, drawings, etc. Six were selected.

Our discussions evolved into concrete ideas for each of the specific pieces. Subsequently, we came up with the final concepts for each of the six panels. Our final decision on the collected research came from various sources and materials. For example, in the Arnoldo’s Brother panel, the image of the young Chicano is a brother of one of the students scanned into the computer from a photograph he brought into class. On his glasses, we see two different images. On the left lens, we see a “border crosser.” This image was taken from the book Five-Hundred Years of Chicano History in Pictures (ed. Elizabeth Martinez). On his right lens, we have another personal image—the grandparents of one of the students. In back of the Chicanito, we see different historical images of Chicano activism.

We see images of women protestors (Viva la Mujer Chicana!) also taken from Five-Hundred Years of Chicano History in Pictures. As a backdrop, we placed the placasos (Chicano stylized form of writing), which was taken from the Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation (CARA) exhibit by Charles “Chaz” Bojorquez from the piece “Rollcall.” Hence, the process of this piece involved a collection of various images that were modified and linked together by us on the computer. The five other digital panels were generated in a similar fashion as the Arnoldo’s brother panel. In some of the other panels, we used slides which were obtained form SPARC’s Mural Resource and Education Center (MREC), the worlds largest archival collection of slides on public art and murals.

The six 8’ x 9’ digital murals were produced in the César Chávez Center Mural Digital Mural Lab located at the Social and Public Art Resource Center, which is equipped with a powerful computer system. Through the use of a flatbed and slide scanner we captured images into the computer, and were able to place, alter, reshape, intensify, adapt and transform images. Groups sat at the computer for hours during class and into the night to produce the images.[/accordion][accordion title=”Tuan’s Parents”]Tuan’s Parents

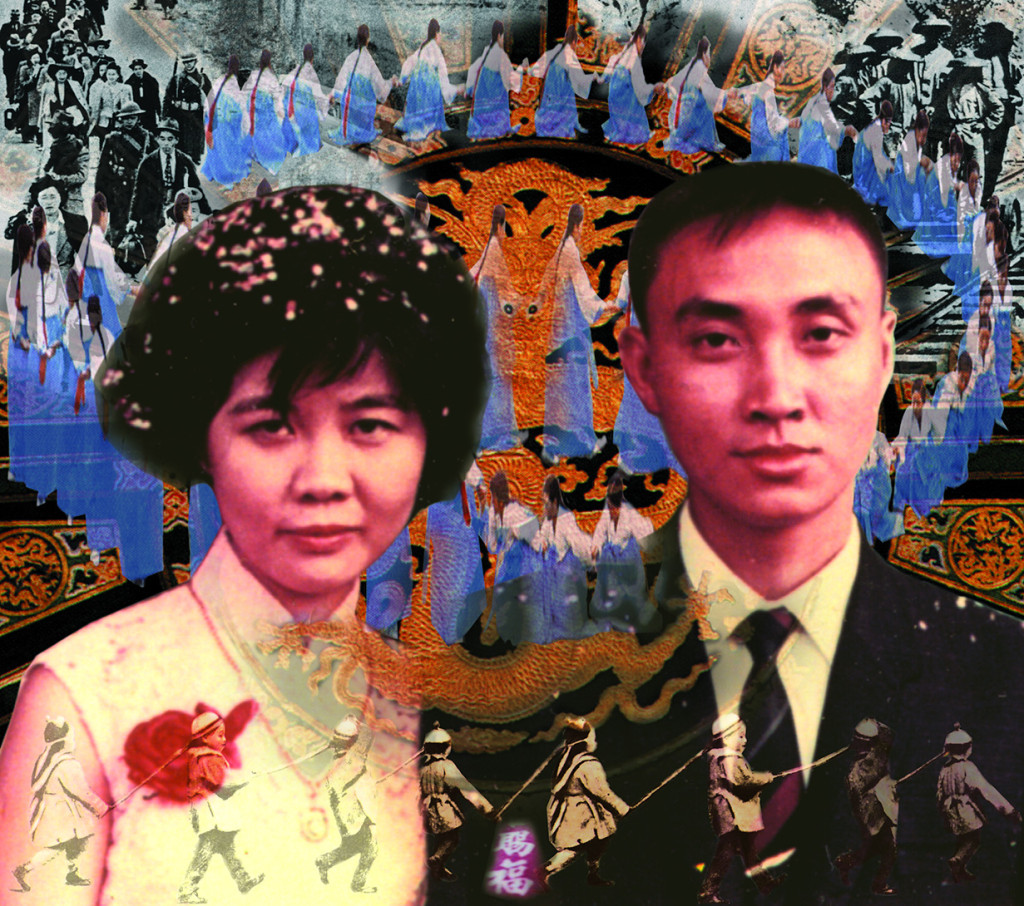

Multiculturalism is reflected in this panel’s representation of three Asian groups: Chinese, Japanese and Korean witnesses to the history of Los Angeles. The central figures represent the youthful, dream0filled newlyweds who will venture forth on a long sea journey toward a better future. A dragon is seen throughout all the images in a circular motion, tying all experiences together in the cycle of life. The images at the right show a group of Chinese immigrants who built the L.A. railroads while being subjected to violence, abuse and disdain. To the left is a WWII image: the incarceration of Japanese-Americans in interment camps, where they were stripped of their belongings and their sense of dignity. Underneath these two images are the Chinese-coolie children who laugh as they march toward work, believing in a better future. The images of the dancers portray a traditional Korean activity that celebrates life. Overall, we wished to show a resilience and strength in the face of hardship and discrimination. Asians are and have been formidable and determined witnesses of L.A.’s history.

[/accordion][accordion title=”Toyporina”]Toyporina – Gabrielino Nation

The Native American witness is a beautiful woman, one of the new mestizas (Indian and Spanish), from the Gabrielino Nation; native to the San Gabriel Valley. (Gabrielino is a name given to the Indians by Europeans—modern descendants prefer the Indian name Tongva.) We chose this woman because we wanted to pay tribute to Toyporina, an indigenous woman who, at the age of 23, led a revolt against the San Gabriel Mission and the Catholic Missionaries.

This panel also pays tribute to all the Native American peoples who, despite past and present atrocities, have kept their dignity and culture, as does Toyporina. The Friars were placed around her to show the constant scrutiny and dehumanization of the native peoples. The tattoos on her body symbolize the countless lives lost and being lost. These are her scars of endurance.[/accordion][accordion title=”Arnoldo’s brother”]Arnoldo’s Brother

We chose a “cholo” as our witness to challenge our viewers’ preconceptions of the Chicano/a and Latino/a in a time of anti-Latino sentiment. The image of this fourteen year-old boy, Arnoldo’s brother, can stir up a firestorm of controversy, yet he is an individual and a child… He stands on a field of what appears to be street graffiti: in actuality, it is a painting of respected Chicano artist Charles “Chaz” Bojorquez; represented in the CARA exhibit.

In choosing this witness, we wanted to propose that our community review its own prejudices and not only learn to understand the struggles of, but to take pride in our youth. Cholos (and the pachucos before them) have historically been scapegoats and much ignored witnesses of Mexican-American culture.

Divisions are constructed of social borders created by our own people a well as the physical borders imposed by others. Our common struggle for education and political power, and against racial assaults on our community – in the form of Proposition 187, anti-affirmative action and growing anti-immigrant sentiment – are all implied in this image.[/accordion][accordion title=”Biddy Mason – the angel of Angel’s Flight”]Biddy Mason – the Angel of Angel’s Flight

There are ghosts – perhaps even angels – that live between the spaces of our lives, Biddy Mason, an African-American woman, is one who walks among us in the Central Market and downtown on Broadway. Biddy, a slave who was freed in 1854, was a community worker who helped people in need. She is the beautiful angel, a ghost on the Angel’s Flight that will remain a part of the story of Los Angeles. Although she is not written into our textbooks, her presence is among us. Here, she is surrounded in the windows of angel’s Flight by images of other people who are and have made history. They are the people who have struggled for justice, equality and truth. They are strong people whose struggles have positively impacted our lives, such as Angela Davis, Rosa Parks, a young woman struggling to get an education, and the Black Panthers. Also depicted is an image of the L.A. civil unrest of 1992, “Freedom Won’t Wait,” by Noni Olabisi. These figures represent fear, rage, quiet dignity and pride.[/accordion][accordion title=”Mr.Pepito: Philipino farmworker”]

Mr. Pepito: Pilipino Farmworker

In the Pilipino witness panel, there are souls in motion. There is movement in the labor of the people and there is celebration in their dance: see the power in their hands and the meaning of their gestures. The depiction of these images reflects the struggles of people who have been part of Los Angeles history. Their dedication, pride and endurance have provided the means to preserve their own history, traditions, and rich culture. The farm worker acts as a column of this city, supporting it on his hard-working back. Theirs are the endless fields that have been harvested. Theirs are the shadows of tall buildings built brick by brick, where the sun cannot warm them. They have overcome the struggles that our society has put before them.[/accordion][accordion title= “The Spirit of L.A. progress”]The Spirit of L.A. Progress

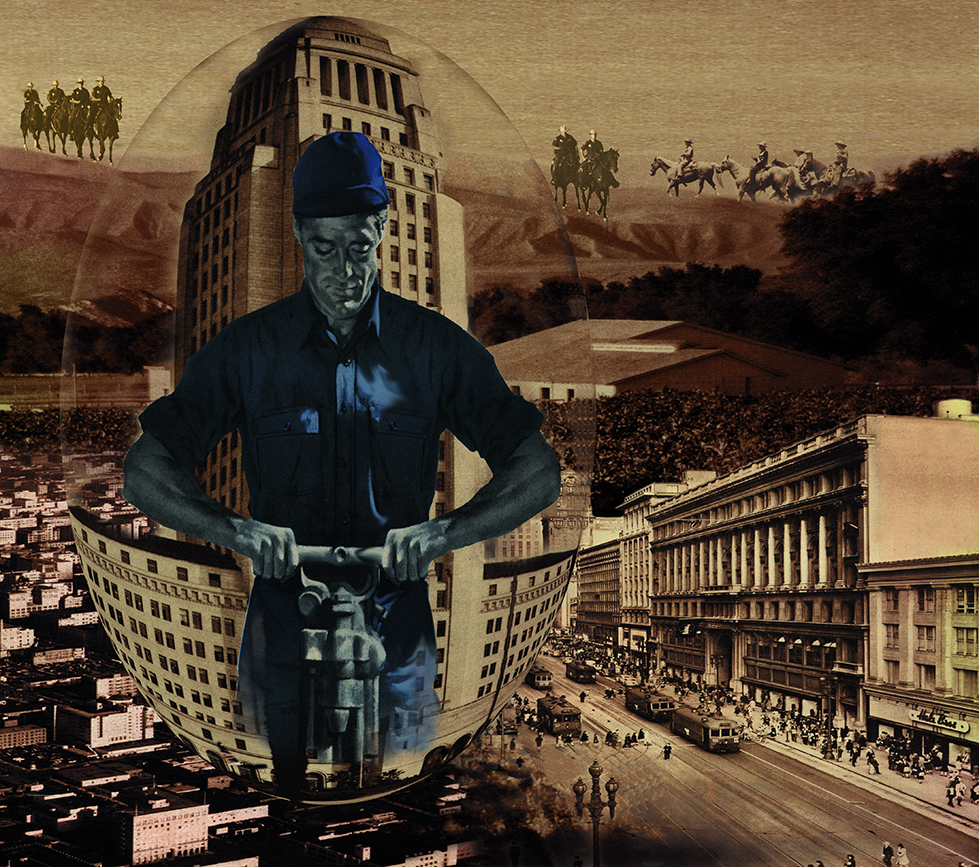

The builders of Los Angeles have hands that have bled into the surface of the earth. All of our witnesses have sacrificed and worked to create the City of Angels. This witness, the blue-collar worker, is encircled by a halo, representing industrialization. Industrialization has brought us modern streets, homes, skyscrapers, airports, freeways – the landscape of today’s L.A. Above the blue-collar worker are men on horseback, overlooking the city. These are the men who have traveled west to build this city. They saw promise in this new land. They worked to change what had been, and to achieve prosperity. They believed in Manifest Destiny – the march of progress and the achievement of the “American Dream.”[/accordion][accordion title=”Reflections”]Reflections

Thrown into a flash of brilliant colors

each staking and claiming his own voice,

I teeter as the rocks beside me slide

I shudder at my thoughts and my alone.

The strength screams its oppositions to death

Throughout, insight is found among the smoke.

Conditions . . . It is time to let go.

Become one, Become Whole.

– Jeanette Conchas

This poem is my tribute to the individuals who, throughout the class, let go of pre-judgments, hang-ups, and stereotypes to unite in a common spirit. Just as in the poem, the power of unity becomes the strength that, together, insists on the death of oppression. There is no longer time to be hampered by conditions in our quest for change; it is time to unite – to become Whole and begin healing.

From the historic “Batalla de Puebla” to The United Farm Workers struggle, history has proven time and again that the power of collaboration is invincible when united by a common spirit and ideal.

This power was exhibited yet again when thirteen students, under the guidance of a professor from the César Chávez Center and two teaching assistants, and with support from SPARC and the Cornerstone Theater Company, became the first class un University of California history to undertake and successfully complete such an ambitious community project – the creation of two murals and six computer-digital panels. Through hard work and team-building exercises, the students who began the project with little in common emerged as a working team with a collective vision. In the span of ten weeks, we learned to make communal decisions regarding various aspects of the production – determining a site, outlining artwork to be produced, development of appropriate images in our drawings, researching accurate ethnic representation for our witnesses to Los Angeles history and exploring symbolic ancestral connections for the Birth and Death panels.

At the end of the ten weeks, the completed series of witnesses to Los Angeles history were installed at California Plaza where they were received with great enthusiasm and appreciation by capacity audiences attending the Birthday of the Century production. A proud reminder of the power of unity and collaboration, they have the ability to transform and inspire everyone who sees them.

Special thanks to my collaborator Laura M. Dueñas, whose responsibility it was, along with mine, to produce this book for our fellow students.[/accordion][accordion title=”About Judith Baca, UCLA and SPARC”] Judith Baca

Professor Judith F. Baca, native Angelina, is a visual artist, an arts activist and a community leader whose vision reflects he spirit, soul and essence of unity among diversity. As a visual artist, her most well-known murals include the “Great wall of Los Angeles,” a half-mile long narrative in the Los Angeles Flood Control District that depicts contributions of ethnic people to the history of America; and “The World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear,” an international traveling mural installation that addresses contemporary issues of global importance; war, peace, cooperation, interdependence, and spiritual growth. A recipient of more than 50 national and international awards, Baca’s works have been exhibited in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Gorky Park in Moscow, El Instituto de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, and other prominent museums, shows and galleries throughout the United States, Europe and Canada, and include a recent commission for the new Denver airport.

Beyond the Mexican Mural is a studio course offered by the César Chávez Center for the first time this quarter (Spring ’96). It provides UCLA students the opportunity to study and work within a community setting in the production of public artworks which link UCLA to the greater Los Angeles community. Taught by senior professor and internationally renowned muralist Judith F. Baca, who has recently joined the six-member faculty currently developing innovative curriculum at the César Chávez center at UCLA, the new course held at SPARC stretches widely held notions of the definition of murals and university education. Incorporating the traditional hand-painted mural and exploring the possibilities of digital production of large-scale images, muralism is taken into the twenty-first century.

The Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) was established by Baca in 1979. SPARC has involved hundreds of artists and the community members in the creation and presentation of public art works throughout the world. Under the Neighborhood Pride Program, over 70 murals have been produced since 1988 in almost every ethnic community of Los Angeles. SPARC’s Mural Resource and Education Center has the country’s most extensive collection of material on twentieth century muralism, with close to 30,000 slides of murals from around the world.

The UCLA César Chávez Center Digital/Mural Lab combines traditional mural-painting techniques with state-of-the-art digital imaging equipment and computer stations. Only ten minutes from the main UCLA campus, the lab is open to students both during and after class hours for work associated with Professor Baca’s classes. The lab is housed in a renovated 10,000 sq. ft. historic deco building, currently home to SPARC, and formerly the Venice police station (1920-1974).

Cornerstone Theater Company was founded in 1986. Cornerstone Theater Company works alone as a professional ensemble and in collaboration with people in diverse communities nationwide. From Kansas to Maine to California, Cornerstone has created two dozen productions that reflect the culture and concerns of distinct American communities involving people of all backgrounds and ages in the creative process, CTC works to help build an inclusive, community-based theater of the United States.

This project represents a unique collaboration between the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), a community-based visual arts organization; the newly formed César Chávez Center at UCLA, an Interdisciplinary Chicana/o Studies Program and Cornerstone Theater Company, a community based performing arts organization. Cornerstone Theater Company’s Birthday of the Century, a new play about a century-long Angelino birthday,

1996 represents the tenth anniversary of Cornerstone Theater Company, the twentieth anniversary of SPARC and the birth f the César Chávez Center.

Colophon

Written by

Laura M. Dueñas and Jeanette Chonchas

Edited by

The entire staff at SPARC including but not limited to Judith F. Baca, Debra J.T. Padilla, Gail B. Schwartz, Lindsey Haley, Alma Lopez, Sara Kicks, Sydney Kamlager and Theresa Deleso-Velazquez

Designed by

Theresa Deleso-Velazquez

And Laura M. Dueñas

Special thanks to Cornerstone Theater Company; California Plaza Presents; Rosina Becerra, Chair of the UCLA César Chávez Center; Center for Instructional Development at UCLA, Sara Kicks, Assistant to the Artistic Director J. Baca at SPARC; Nestor Martinez; John Mishkanian at Megagrafx; Debra Padilla, SPARC Managing Director; Raymond Paredes, UCLA Vice-Chancellor; Jeff Stansfield and Advantage Computers; Scott Waugh, UCLA Dean of Social Sciences; Sister Java and Columbia, for her extraordinary energy; and especially to the continuing spirit and inspiration of César Chávez

Class support staff

Alma Lopez, Artist and César Chávez Center Research Assistant

Omar Ramirez, Artist and Computer Tech

Solomon Huerta, Artist and Teaching Assistant at the César Chávez Center

Artists

Rogelio Pacheco Chacon, Jeanette Conchas, Laura M. Dueñas, Erin Rose Flood, Jason Albert Garcia, Jennifer Lynn Granado, Tuan Thien Hwang, Patricia Nelson, Angelica Pereyra, Anissa Nicole Reichle, Mario Adam Rodriquez, Arnoldo Vargas, Darlene Worley, Eric Erestingtom, Alma Lopez, Omar Ramirez, Salomen Huerta, and Professor Baca

Sponsored by UCLA César Chavez Center, Social & Public Art Resource Center, Cornerstone Theater Company and made possible by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation[/accordion]