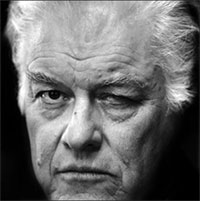

En La Memoria de Luis Jimenez

Luis Jimenez

1940 – June 13th 2006

Dear friends and fellow artists,

We have lost our companero Luis Jimenez too soon. The great Chicano Sculptor whose work appears in public sites throughout the country was killed in his studio yesterday in a tragic accident involving a hoist and the 28ft mustang in progress for Denver International Airport. Luis was among the first Chicanos to become a public artist producing unforgettable works of art representing the southwest Chicano experience. He gave us the unforgettable images in public spaces of immigrants crossing the border in Cruzando el Río Bravo, the Mexicano cowboy in El Vacquero or the local lore of the alligators in El Paso in the Plaza de Los Lagartos. These artworks and many other monumental works of art along with his beautiful drawings and lithographs made up the rich legacy of his work. Luis was and is a true “icon” not only of Chicano art but American art.

For many of us he was a great friend and continual inspiration. Luis was among the most generous of artists in his ability to represent his culture and the experiences of his people along the border and throughout the Southwest. We shared a belief that our work needed to be a witness to another truth often not told by re-envisioning a history of “inclusion” depicting humble but heroic people of our everyday lives. I loved best his beautiful drawings and lithographs which were simultaneously compassionate and critical. Luis’ lithographs on the issues of the border are currently on display in our Hub. In 1992, SPARC hosted a retrospective of his work here in our gallery please see our posted catalogue of his work.

Judy Baca

Artistic Director

Social and Public Art Resource Center

June 14, 2006

Article from the El Paso Times

Catalogue of Jimenez’ Solo Exhibitions at SPARC

[accordiongroup][accordion title=”Bio”]

Growing up in a barrio of El Paso, Texas, Luis Jimenez learned about art by reading books, working in his father’s electric and neon sign shop, and visiting museums and murals in Mexico City. When he eventually embarked on a formal study of art in the mid-’60s, Jimenez found reactions to his subject matter less than encouraging.

” ‘Oh my God,’ people told me. ‘Serious artists don’t work with cowboys and Indians and little horses and things,’ ” he recalls, laughing.

Today, the sculptor’s mammoth fiberglass depictions of cowboys and Indians have won him national acclaim, including a slot in Texas Monthly’s “Texas Twenty,” a list of the “most impressive, intriguing, and influential Texans of 1998.” One of his “little” horses, a 32-foot-tall mustang in progress, has a prime spot next to the main terminal at the Denver International Airport. Jimenez began making large-scale public pieces after he “arrived” on the New York art scene of the late ’60s. His first one-person exhibition at Graham Gallery in 1969 was a success, and after years of struggling, he was finally able to support himself through his art.

Perhaps because he’d spent his lean years in New York City working in minority youth programs, or because the beloved artists from his childhood were public muralists like José Clemente Orozco, Jimenez wasn’t content to succeed within the exclusive realm of private collectors and galleries. “I think there has always been a group of people that responded to my work, but because of the way the art world operates, they probably couldn’t afford it,” says Jimenez. “With the public pieces, they don’t have to buy it. The works are sitting out in a public place.”

Working in New York from 1966-72, he drew on East Coast images for his subject matter. But when he returned home to the Southwest, he adopted the symbols of his home region: vaqueros, Indians, farmers, and rodeo queens. These remain his inspiration as he works from his home/studio, a converted schoolhouse in Hondo, New Mexico.

Called “revisionist history,” Jimenez’s public works aren’t designed to create controversy, but they do. Of his most famous work, Vaquero, he says, “The cowboy has a gun because equestrians are always pictured with either their sword or their gun.” So Jimenez was surprised when two of the sites for which Vaquero was intended were rejected and replaced with alternate sites because of the vaquero’s weapon. The specter of a gunslinging Mexican cowboy, violent and menacing to some, was Jimenez’s answer to the traditional military monument. “No one would dream of taking away Robert E. Lee’s gun or George Washington’s sword, but somehow the thought of a Mexican with a gun is seen as a big threat,” he says.

[/accordion]